57歲女性教師 到急診的原因主要是因為胸悶及頭暈的情形

這樣的情形是在跟一位五年級學生的家長吵架完之後產生

而當這位教師回到家中 其先生幫她量血壓 發生只有80-90mmHg的收縮壓

就趕快送到急診

追溯其過去病史 只有高血壓的問題 血壓使用lisonopril 5mg QD控制得不錯

在急診時 其生命徵象:BP:83/50 mm Hg,HR:110,RR:14,Sat:99% under nasal 2L/min

身體檢查:無頸靜脈怒張 肺部無囉音 乾淨

but a loud, crescendo systolic murmur,best heard at the right upper sternal border

其他部分都是正常

Lab at ER:Hb:11.1,platelet:190000,WBC:10300,BUN:17,Cr:0.7

glucose:106

急診所做的ECG如下

finding:ST-segment elevations of 1 to 2 mm in leads V2 to V4, with a biphasic

T wave in V3; and deep, symmetric T-wave inversions in leads V4 to V6

CXR at ER

Finding:bilateral pleural effusion with Kerley B line(APE)

因為EKG顯示STEMI,當時馬上給予aspirin及使用IV heparin

後來出來的Cardiac enzyme:CK-MB:14.1,Troponin-I:4.23

因為STEMI故急安排PTCA

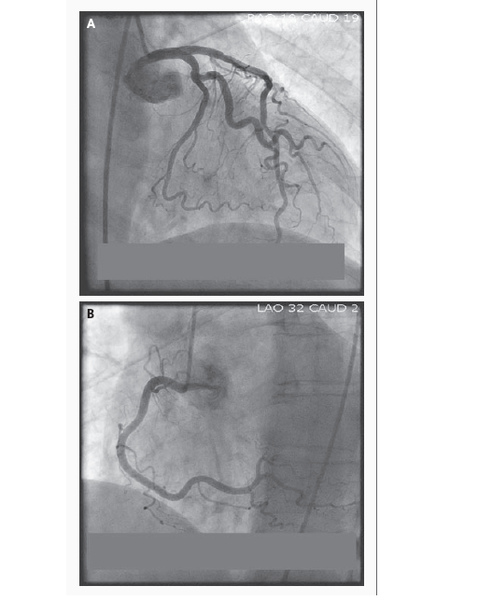

Cath如下:

並沒有發現明顯的stenosis及thromobosis,plaque rupture

在左心室收縮時及主動脈間 有明顯的壓力差 約49mmHg,LVEDP:30mmHg

LVSP:123mmHg

LV ventriculography:

Finding:severe distal anterolateral, apical, and diaphragmatic

dyskinesis with hypercontractile basal segments.

Moderate MR,EF:35%

因為STEMI,病患被轉送至ICU 之後胸痛症狀緩解

生命徵象穩定

follow up Cardiac echo showed:ejection fraction of 35%;

moderate mitral regurgitation with systolic anterior motion of the leaflet;

and mild ventricular systolic dysfunction with akinesisof the apex,

mid anterior wall, mid anteroseptum,mid septum, and mid posterior wall

病患於四天後出院 於一個月後回到門診

回家後並沒有任何心臟衰竭的症狀

也沒有喘及胸痛的情形

追蹤的cardiac echo發現:left ventricular hypertrophy with normal left ventricular

function, an estimated ejection fraction of 75% and resolution of the mitral regurgitation

診斷:由於完全的恢復在一次的STEMI episode後 及心導管上並沒有發現血管栓塞的情形

且在心室攝影上發現hypercontractile basal segment

及severe dyskinesis of apical segment 形狀就像tako或ballon一般

加上病患的發作是在一個壓力的情況下產生 最終的診斷為:

Apical balloning syndrome

---------------------------------------------------

Features of Apical Ballooning Syndrome

Apical ballooning syndrome (also described as tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, and the broken-heart syndrome) is an increasingly recognized condition that can closely mimic acute myocardial infarction. Its incidence is estimated to be 1 to 2% among patients who present with a presumed acute myocardial infarction. It classically affects postmenopausal women in the fifth to seventh decade, and the onset of the condition is often precipitated by emotional stress. Key features of apical ballooning syndrome are the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease in the setting of characteristic “ballooning” of the left ventricle from severe anteroapical akinesis and hypercontractility of the basal segments. Heart failure is present in approximately 50% of patients with apical ballooning syndrome, and cardiogenic shock occurs in up to 15%. Approximately 20% of these patients also have a transient systolic murmur associated with subvalvular pressure gradients that can mimic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

Diagnosis of Apical Ballooning Syndrome

Although it is critical to differentiate apical ballooning syndrome from acute myocardial infarction quickly, it can be challenging to do so. There are no electrocardiographic findings that clearly distinguish apical ballooning syndrome from acute myocardial infarction. With apical ballooning syndrome, the elevations in troponin are typically much lower than would be expected on the basis of the wall-motion abnormalities. However, it is difficult to rely on cardiac biomarkers alone, since these are often only modestly elevated during the early stages of an acute myocardial infarction. Thus, the diagnosis frequently becomes evident only in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, when no angiographically significant coronary artery disease is found. It is generally not advisable to withhold antithrombotic treatments such as heparin and aspirin while the diagnosis remains uncertain, since acute myocardial infarction is much more common. Decisions about fibrinolytic therapy are more complicated, given its associated risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. Whenever feasible, emergency coronary angiography should be performed to assist in clinical decision making.

What is the pathophysiology of apical ballooning syndrome?

A: The pathophysiology of apical ballooning syndrome has not been clearly elucidated. Leading hypotheses include transient catecholamine toxicity, aborted ST-elevation myocardial infarction with spontaneous lysis of thrombus, coronary vasospasm, and microcirculatory dysfunction. Similar wall-motion abnormalities have been seen in other states of catecholamine excess, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage and pheochromocytoma.

What is the recommended treatment for apical ballooning syndrome?

A: In patients with acute outflow tract obstruction, treatment should focus on ensuring adequate intravascular volume. Beta-blockers may also be considered in an attempt to slow the heart rate and increase the diastolic filling time. Although data from clinical trials are scant, some experts suggest treating patients with apical ballooning syndrome with beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting–enzyme inhibitors until left ventricular systolic function normalizes; it has also been hypothesized that treatment with beta-blockers may reduce the risk of recurrence (which is reported in a case series to be approximately 10%). Inotropic agents should be avoided, since they may exacerbate the outflow tract gradient. Aspirin should be considered for patients who have coexisting coronary artery disease. Some clinicians recommend anticoagulation with warfarin for several weeks in patients with severe systolic dysfunction in order to prevent left ventricular thrombus formation. In most patients with apical ballooning syndrome, the condition improves rapidly with supportive measures. Complete recovery of systolic function is typically observed within 4 to 6 weeks, and the overall prognosis tends to be excellent.

留言列表

留言列表

我的部落格蒐藏

我的部落格蒐藏